Here's What The Working Class Thinks About America (Picture)

"I’m from here, but I feel more Mexican than American. Me and my twin brother were born in Hollywood, but my parents are from Mexico, from Chihuahua; they came 25 years ago. I’m more comfortable speaking in Spanish than English. My wife is also from here, and she speaks only English — and I answer in Spanish.

"It’s different for immigrants now. There are new laws. It’s harder to get here. Everything is much more expensive. Many families don’t have any support in their countries. And then they arrive and don’t know anything. It’s not easy to get a job if you don’t have legal documents. It’s hard nowadays."

Sam Comen is a Los Angeles–based photographer who has a seemingly insatiable curiosity about people. His work often centers on broad collections of portraits, allowing the viewer to draw their own conclusions about what it means to be a citizen or an activist. One of his recent projects, Working America, takes an inclusive look at the intersection between being an immigrant and a worker. The series, which Comen started over two years ago, draws on inspirations from the turn of the 20th century when immigrant-owned small businesses were the norm and highlights how valuable this work still is within the Los Angeles community.

Can you talk a bit more about why you chose to focus on mostly immigrants in small trades?

We’re all immigrants on this continent, except for the descendants of Native Americans, but we have a complicated past and present with immigration. There’s always been a streak of xenophobic nationalism running through a segment of our population and culture that the forces of social and technological progress periodically check. With WA, I contemplated the experience of my own family. As Jews, did they fit into the idea of “white respectability” or align with Protestant and Baptist notions of America when they immigrated in the late 19th century? Donald Trump has aggressively ushered in a new low in anti-immigrant feeling in post-WWII America. It’s clear that the rigid, intolerant stance he’s enabled isn’t aimed at all immigrants and families who’ve recently naturalized, but reserved for non-Christians, those without significant wealth, and especially for people of color.

Focusing on the small trades felt like an authentic way to recall the celebrated 19th and 20th century immigrant entrepreneurialism our nation is built on. This project’s portraits draw out the personality and perseverance of the subjects, wrapped in the attributes of their work. They are comparable to my great-grandparents and driven by the same ethos of prospering through the American dream. They are makers, service workers in small and medium businesses, artisans with honed crafts — talented, industrious people contributing to local economies. There’s also a photographic tradition in documenting the small trades. August Sander most famously attempted to archive identity in work, class, and marginalization in Germany between the World Wars. Irving Penn bounced from Paris to London to New York in an effort to celebrate worker roles and to convey the unique postures and garb of those cities. WA honors an analogous past. But it breaks untapped ground by directly grappling with a question at the intersection of contemporary immigration and American capitalism, namely: Is trade work (of any kind) a genuine path to economic independence and inclusion for non-European immigrants and first-generation Americans?

Cynthia Patricia Aguilar, chef and server

"Once you immigrate here, you find freedom, right? But it's like there's no freedom. I don't think that's the American way, for ICE to come into our home and take a parent away. And you have kids there? It’s pretty much mind-boggling. What's going on? It's sad. It's not humane at all. You can be here and you go through all that, and you're thinking, Yes. I'm here. You see the lights, you see the roads, you see everything, and you see people, and it's not it. Once you're here it gets harder.

"There's a lot of hate. I think politicians are just making people more angry now. People are going against each other. We already saw that, but it's just getting worse. Each and every day, you hear something new, and it's scary now."

How many people did you interview for this? How did you find people to participate?

It’s interesting to look back. I count 47 separate sittings, some with multiple subjects. I went door-to-door, starting with businesses in the neighborhood where I was born and have spent my adult life, Los Feliz. Some of the businesses were my local go-tos and others I’d walked by for years without a single visit.

To create connections with the subjects, I did what I always do: I share my project’s intent and I share the questions I’m asking to see if they resonate with that person. From there, we shoot right then or schedule a time. I’ve also hired assistants to approach subjects across Los Angeles, helping me canvass to achieve geographical reach and connect with a diverse array of immigrant and first-generation communities.

What were some common themes you encountered?

Most of the subjects identify as American and feel American because they believe that America is an idea to embrace, as much as a land mass. There’s a sense that pursuing opportunity, contributing, and believing, regardless of the kind of work you do, in an equality of humans — that no one is greater than anyone else — are what makes a person American. They want their status to be uncontroversial and for their American identity to not be a point of contention and debate. “It’s frustrating that we're still considered immigrants or descendants of immigrants, because we're just...American,” said Chris, a first-generation bookseller who captured the thoughts of many of the subjects.

Another theme revolved around paying it forward. There was widespread gratitude for the struggle, sacrifices, and work of their parents, who made being “first-generation” possible. They wanted to provide even better opportunities for their own children.

Positive mantras around working hard, respecting each other, loving your neighbor, setting an example, and pushing yourself were common too. But it’s also worth mentioning that several individuals felt that vocal hatred, complications around documentation, and fear of ICE have made life more of a struggle in the past few years.

Young Ae Jung, tailor

“In Korea my husband passed away in an accident. I was sad and unable to work. And I stayed alone for long amounts of time. Since I already had a good impression of the United States, I decided to move with the help of family members that were already here and have a fresh start with my children.

“The idea of loving your neighbors and sharing the wealth with people is important to me. I think of the US as a country built upon this idea, and so I love the US.”

In your project statement, you say, "I’m curious if the national trope of hard work as a path to economic independence and inclusion is a reality." Did your impression of what it means to be an American, or the idea of the American dream, change while working on this project?

Many of the subjects have come from places where opportunity is extremely limited and hardship is ubiquitous. So, in some of their perspectives, there's a kind of stoicism toward intolerant behavior and America feels like a more hopeful place in general. For some, there was a feeling that Trump’s rhetoric wasn’t much different than that during other conservative administrations. A few of the individuals hadn’t experienced much adversity since arriving. My initial assumptions about race and class impacting access to economic empowerment negatively for all were tempered by the subjects’ actual experiences — those ran the gamut from feeling bigotry and condescension in a direct and damaging way to finding, with relative ease, work that supports a decent standard of living and an affirmative sense of belonging. Photographing these individuals gave me an intimate window into their lives for a contemplative moment. Their desire to be American and to make life successful here means, for me, they are American.

What was it like seeing this work featured at the DNC?

Knowing there’s alignment between my point of view and the Biden campaign’s platform on immigration was wonderful. My view is that immigration is core to our American experiment. It’s a key part of what makes this nation special. That all Americans and those who want to be Americans are worthy of everyone else’s respect is a deep strength of ours, a value we need to vigilantly nourish and cherish. I make work to explore issues, express my view and learn others’ views, and examine our shared society at the intersections of politics, culture, and art. When I put the work in front of people, it’s my deepest hope that it resonates with them and they feel compelled to spread it, question more, and spur empathy. That’s what happened with the Biden campaign and I’m grateful.

Hisham Abahusayn, set electrician

“People learn from their parents and neighbors, and they form opinions about the world because of the circles that they’re in. That’s petrifying. I have an 11-year-old son. I feel like I gotta train him for discussions and arguments that he’s gonna have based on his name. That’s really scary, that we live in a world like that. I thought when I was younger, it was going to be the exact opposite, but now it’s just 'them' and 'us.'

"But I’m confident that we will overcome this obstacle. And I'm actually really optimistic because I think that this moment is showing us what is really going on underneath the surface.

"I know that I'm an American: I don't care what other people think an American is or not.”

You've talked a bit about these images being a part of the historical record, which several museums seem to agree with. How do you hope that future generations see this work?

Hopefully they will see it as an early 21st century continuation of and homage to the artful documentation of immigrant and worker experiences that Eugène Atget, August Sander, Dorothea Lange, Irving Penn, and others established. The high-speed, color photography and slow-motion videography I’ve used seem to fit our era of technological innovation. That tool shift creates a new chapter in this genre’s story, but the core elements — composition, lighting, expression — that make a good picture have not changed.

It’s possible that many of the jobs portrayed in this body of work will disappear as our consumer culture shifts. Penn knew the horse-drawn carriage coachmen in London would fade as a commonplace vocation. That’s why he photographed them. Likewise, this set of work will be a time capsule. As commercialism and cheap production continue to move us toward disposable goods, fast fashion, and same-day delivery, will repairmen have work? Will tailors have work?

Mario Rosales, baker

"The truth is I don’t know [what’s wrong with the current administration’s vision on immigrants]. Like I said, there’s a lot of us who do things we shouldn’t, but there’s a lot of people who do need help, and I know a lot of people who have arrived, go to school, and don’t have legal documents, but you see, they make an effort. I’d like the government to help people, but they should check who they are first, how they live.

"Mexicans who haven’t been here think they can come, and everything will be easy. And it’s not. Not any more."

Do you have a favorite image you want to talk about?

It’s really tough to choose one because there are unique and compelling personal stories and certainly beauty inherent in all of them.

The portrait “Jesus Sera, Dishwasher” won second prize in the Smithsonian’s 2019 Outwin competition, out of 2,600 entries and 46 finalists, and is now touring the US through 2022. Taína Caragol, the National Portrait Gallery’s curator of Latino art and history, described that image beautifully, to my mind. She wrote, “Against a forest of kitchen utensils and stainless steel, his gaze directed upwards and bearing a slight smile, Jesus Sera projects dignity and pride. … [Sam’s] photographs of behind-the-scenes laborers, such as dishwashers and shoemakers, acknowledge his sitter's contributions to society.” That’s what I wholeheartedly aim for.

Monica Botsio Essandoh, tailor

“I have achieved the American dream, I was able to go to school, [with] financial aid. And then they help you. If you are willing to learn, they will show you the way. Nobody is going to take a bribe or deprive you from your aspiration. And if you have that in mind that you're going to make it, you make it. Some people come, they don't even understand a single English word, but still they can go to school. It's all determination.

“We’re all equal. Everybody has potential. Everybody has something to do, just for us all to be happy. Somebody can be cleaning the streets, somebody can sweep, somebody can be a lawyer. If everybody's a lawyer, who is going to sweep? Who's going to be a nurse? Who's going to sew the clothes?”

Boris Macquin, waiter

"In the work that I do, you can really see that structure — of whoever is Hispanic, where they work, and whoever is white — where they work. You know, I feel like I'm an immigrant, but I feel like I have more chance than other immigrants. I work in front of the house, and I would say the Hispanic people are in the back of the house, and that's how it kind of is. And I probably make more money. And it's not necessarily fair, because some of them have been here longer than I have and speak better English.

"I think I fit in, at least as far as my physical appearance. So I don't think I had too many problems getting here, but I could see how some don't have that chance."

Sharon Choi, landscaping tool repair shop owner

"When we started this business in 1990 we were at zero. My husband went to school at night and he wouldn’t even have a 25-cent cup of coffee from the vending machine. Compared to that time, now we’re living in luxury.

"We’re working here now not only to make money, but to help others. That’s my duty, I believe, with what God has given to us. I don't know how others define real success, but to me real success is following the Bible, focusing on living an honest life every day."

Othon Gonzalez & Mher Shorhokian, glaziers

Gonzalez (left): “My stepson — the oldest, 16 — was in therapy because with my immigration problems, they came to my house to detain me and I was in custody for a week. His grades dropped and he was really worried. He lives in a constant fear that they are coming back and we are going to be separated. And when I have appointments, he begins to pop his fingers and is constantly biting his nails, he is so nervous.

“When I retire, I want my children to continue the legacy. That it goes from generation to generation, as they say, so this can grow.”

Shorhokian: “When I came from Beirut, I didn't bring anything. I start with zero. I have to work, to keep the family. Glass was a family business. I put a small ad on Yellow Pages and somebody called me — his name is Frank. I make a small job for him and he ask me, ‘You have any shop?’ I say no. He say, ‘Follow me.’ I follow him to Kenmore and Hollywood, and he told me, ‘Just stay here.’ He told me, ‘Open the shop for three or six months, free. See if you can work. If you don't like, give it back, without money.’ I just say, My God, he gave me the way to work. That's why I start my business, 1703 North Kenmore Avenue, 1986, April 24.

“In America I was new, I didn't know the ways. It's a very big country. Lebanon is very small, everybody knows us. If you come to America, nobody knows you. And to know you, it takes a long time.”

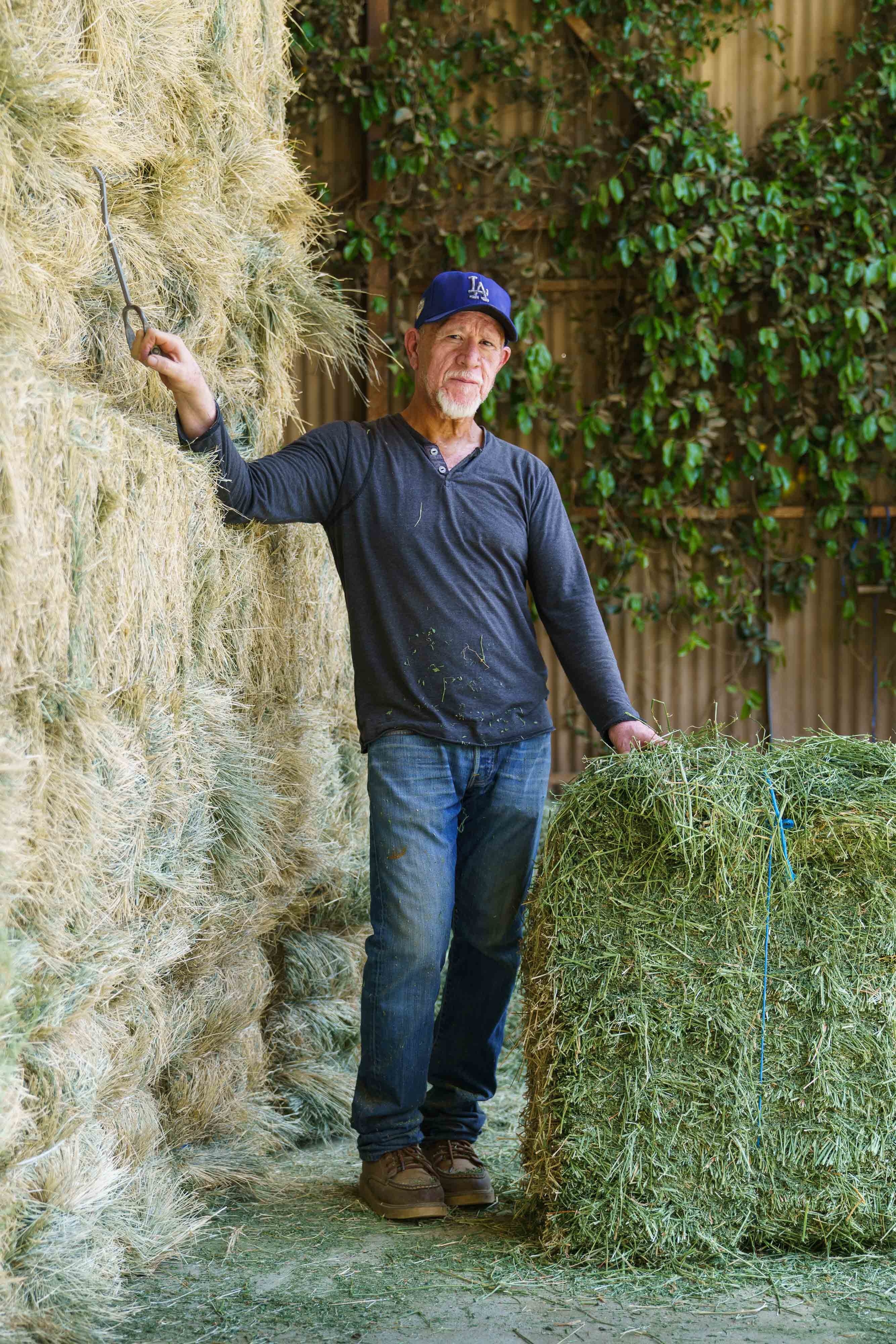

Antonio Gomez, ranch hand

"My parents saw a lot of opportunities back then. And that's why they brought me back here and put me to school. A lot of people, they don't have dreams. I had a dream to get a house and better my life, and I want my children to have a better life.

"I'm doing what my parents taught me: ‘do better.’ Wherever you go, make a difference. California is a place of opportunity. Opportunity comes and you got to grab it, and don't let it go. A job is a job, and a career is a career. What do you want? Do you want to make something out of your life? Here are the tools. You just got to come and get it. That's my frame of mind."

María Leonor García & Elizabeth García, restaurant owner & manager

Leonor (left): “Honestly, right now, it’s undesirable to come. In Mexico, you know how immigration is: just like here or worse. They only see that you’re a foreigner and…even the Latinos here, they’ll point you out, and they’ll call Immigration on you, and they’ll take you out. You’ve already lost a lot. And many people don’t think we’re here to work.

“When I started out, the restaurant was worthless, but I knew I could make it grow. Of course, I worked a lot. I’ve never wanted to have much, but I’ve had it all. And my children always had all they needed.”

Elizabeth (right): “I tell my kids every day to look at grandma and be grateful, because unfortunately she was never there for me. She missed half of my life. She didn't attend my sixth-grade graduation, any of my competitions, she almost didn't attend my high school graduation. It was because she was at work from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. And now I am able to attend every one of my child's sports. I have everything because she struggled, and I am forever grateful for that.

“Look into history. Look into your own family. You know, there's bits and pieces of your own story that would change so many aspects of your life if you really went back and looked at them.”

Safwan Almalki, valet parking attendant

“I feel if I do a good job and if I work hard and if I'm studying hard, USA gonna say “welcome’ to me for sure, 100%, because USA, they want good people, 100%, they don't want bad people. So I have to be clean and clear, all my CV clear. Like maybe one day, I'm trying to live here, to find work here, to get a green card, to work, to do anything.

“If you work on it, if you give all your energy to your goal. So if you have a goal, you have to put all your energy, focus on it, work hard, hustle, do anything to get there, to get it, just focus on it.

“In America, if you give all your energy to what you want, it's gonna be true.”