After Serving at Ground Zero, Going to Afghanistan ‘Felt Right’ to These New Yorkers

William Snyder still remembers the acrid smell of burning jet fuel and crushed concrete mixed with the dust, soot, and ash that covered virtually everything at Ground Zero.

He remembers daily walks past the rubble where the Twin Towers had been, and the smashed and twisted hook-and-ladder truck, and realizing that anyone who’d been inside it almost certainly could not have survived. He remembers the windows blown out of the surrounding buildings, damage not captured in much of the TV footage, and the office paper blowing through the streets.

Snyder had been teaching eighth-grade history at a school about seven hours away near Buffalo, N.Y., when terrorists attacked the United States on September 11, 2001. He was one of more than 4,000 New York National Guard members mobilized that Tuesday 20 years ago.

In the days that followed, Snyder’s unit was assigned to guard the Ground Zero perimeter, Wall Street, and the heliport in lower Manhattan. He was only 24 at the time, then a specialist in the Guard. Now, he’s a lieutenant colonel.

Some days, between shifts, he would stop and watch first responders digging through the rubble. “It’s sort of hard to put into words, but it was tough, definitely tough,” Snyder told National Review.

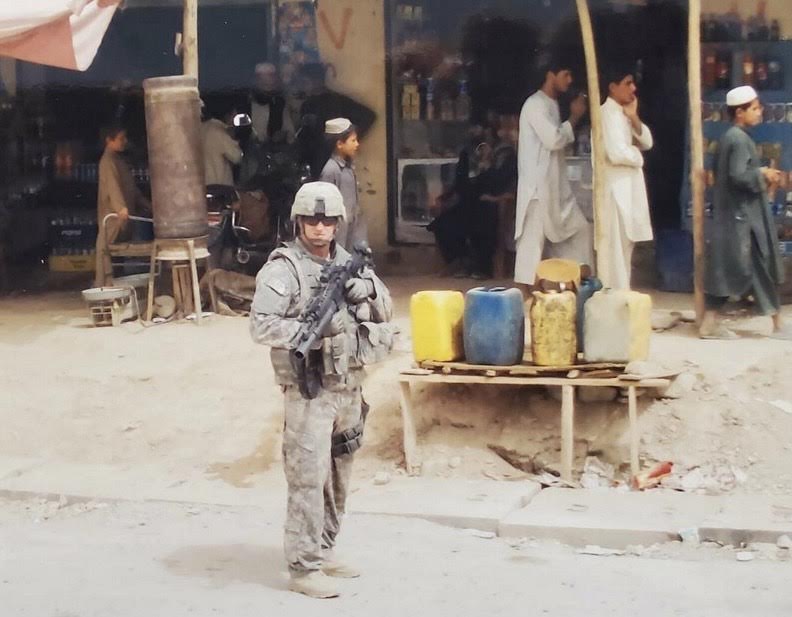

Snyder’s connection to the September 11 attacks didn’t end when his unit was rotated out of New York City. Seven years later, Snyder’s 27th Infantry Brigade was sent to Afghanistan, where the attacks were planned. Their mission was to train members of the Afghan military and national police. “For a group of New Yorkers,” he said, “to go to Afghanistan, it sort of had this, it felt right, the right thing to do. It made sense for us to deploy there, almost a sense of payback, if you want to call it that.”

Snyder, 44, is one of a select number of people, many of them New Yorkers, who served both in the immediate aftermath of the attacks in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pa., and then again overseas in Afghanistan or Iraq as part of the War on Terror.

Over 14,000 New York National Guard soldiers and airmen were involved in the 9/11 response, according to the U.S. Army. A number of them later shipped off to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq. Some of the police officers and firefighters who responded to the attacks would also later deploy, including New York Police Department detective Joseph Lemm, an Air National Guard sergeant who was killed in a suicide bombing in 2015 in Afghanistan. He was on his third tour of duty in the Middle East. Lemm is one of three New York City police officers who were killed in Afghanistan or Iraq during the War on Terror.

Micah Lyness, who joined the New York National Guard after high school, eventually full-time, also went to Ground Zero before serving two tours in Afghanistan with the 27th Infantry Brigade.

Lyness, 46, recalled that only about a month before September 11, he and his family had taken a trip into the city, where they visited the Statue of Liberty, went to a Yankees game, and took pictures on the roof of the World Trade Center. “Being in the city the month before, standing on the tower, that definitely was kind of personal,” he said.

When he went back to the city in the wake of the attacks, he said the area that was now Ground Zero was almost unrecognizable. The building he’d stood on was gone and the Lexington Avenue Armory was covered with missing persons flyers.

“I remember, definitely, the smell. There was definitely a smell down there that was nothing like I’d ever smelled before,” said Lyness, who was a staff sergeant at the time. “It was definitely a surreal experience being down there and seeing the destruction, and how wide Ground Zero actually was. It took a couple days to kind of understand the magnitude, or come to grips, I guess, with what you’re seeing.”

As a full-time and trained soldier, Lyness hoped to be deployed overseas in the U.S. response to the attacks, but he wasn’t confident the National Guard would be utilized that way. It often hadn’t been in the past. “Not knowing how big and how long this war on terrorism was going to be, at that time I wasn’t sure,” he said. “When they decided to go into Iraq, that’s when they really started hitting the National Guard for troops.”

Lyness was at one point on a deployment list for Iraq, but he got pulled off because they needed some full-time Guard members to stay back. Lyness was upset initially. His brother went to Iraq, as did many of his friends.

“You didn’t want to be the guy that didn’t go. I ended up being that guy that didn’t go,” he said.

But he did end up going to Afghanistan. Twice. In 2008, he was a sergeant first class and part of the mission to train the Afghan army and police. He was in a couple of firefights, but “everybody came through with all their limbs and digits, and nobody got killed with my group,” he said. In 2012, Lyness was a first sergeant of an engineer company tasked with finding and clearing improvised explosive devices off of roads. His company earned accolades for combat action, though Lyness said he spent less time on that tour “out of the wire, fighting the fight.”

Lyness retired from the National Guard in 2018, and now works for the state of New York helping veterans get their hard-earned benefits. As for the end of the war in Afghanistan, he described himself as “kind of a realist, I guess.” According to Lyness, the Afghan government didn’t do much for its citizens, and the people didn’t identify with it. “I didn’t have high hopes that it was going to be some sort of great democracy,” Lyness said.

“Pulling people out, that didn’t really matter to me. It was upsetting for sure to see the manner in which we did it. I don’t understand it,” he said. “I look at it as, ‘Yeah, I got you, we’re leaving, but we’ll leave when we have everything done that we need to have done to get our people out, to get Americans out, to get our friends that have helped us the past decade.’”

“To me, we’re the U.S., we set the rules, especially with the Taliban,” he said, adding that even after pulling out of Afghanistan “the terrorists still want to kill Americans.”

Snyder agreed that the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan was difficult to watch. He doesn’t know what happened to all the Afghans he worked with when he was overseas. It’s his understanding that a lot of soldiers and former soldiers are struggling to process what happened.

“I completely understand that. It’s an emotional thing to watch,” he said. “But I will say that I truly believe that for 20 years that we were in Afghanistan, and even the year that our brigade served … I truly believe that helped keep America safer. We were doing the right thing.”

Snyder separates his time at Ground Zero from his time in Afghanistan in his mind.

“I don’t think ending the war in Afghanistan is going to change the way you think about 9/11, because we did get Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda was definitely decimated for a long time,” he said.

Snyder still teaches eighth-grade history at the same school where he worked on September 11. He still talks about the attack in class every year. He used to have dialogues with his students about what they were doing and feeling at the time, but the kids he’s teaching now have no personal connection to it. September 11 was just another thing that happened before they were born, like Vietnam or World War II. “It’s just a different feeling,” he said.

Snyder believes his service at Ground Zero and in Afghanistan has made him a better educator. When he teaches about war, he can teach with the confidence that comes from first-hand experience.

No comments